Translator at an Exhibition

Blog review of current and recent shows in Dutch museums

Willem Witsen at Museum Jan Cunen in Oss succeeds making us feel a powerful stillness

18 Feb thru 16 June 2024

By imposing a frame around a subject, western art automatically elevates a sitter or scene. But what if as an artist you wanted to focus on the unnoticeable without ruining its very nature? The paradox of depicting mundanity seems to have obsessed nineteenth-century Dutch painter Willem Witsen (1860-1923), an artist of out-of-the-way places, whose powerful stillness is the theme of a quietly intriguing exposition at Museum Jan Cunen.

Witsen was a master of different media – oil, watercolour, etch, and the gelatine dry plate negative that revolutionized photography in his time. He repeated the same or similar scenes and the exhibition’s curator invites us to look again with Witsen at the same Amsterdam street or woodland scene in a different medium. We are also invited to compare Witsen’s work with that of his friends and contemporaries, painters like Isaac Israels, George Breitner and others of their circle. This was the time of the young arts movement of the eighties (De Tachtigers), and handwritten letters between artist and writer friends are displayed on old-fashioned writing desks set up in each room of Huize Constanze, allowing us to eavesdrop on their personal lives as we journey through the exhibit.

What kind silent power is held in these works? And how did Witsen achieve this effect? Wandering from room to room, what the viewer notices is a theme of stillness achieved through stasis, tiny freeze-frame figures or none at all, a muted monochrome palette, and a particularly damp and cold atmosphere, often scenes of fog or snow. Witsen was from the very beginning a “bad weather” artist, something inspired and perfected on an early visit to London in 1888-1891. His nocturnes (possibly influenced by Whistler) show us sepia-toned watercolour scenes around Waterloo Bridge and the Embankment. One view beside the bridge where two walls form a massive corner juxtaposes detailed brickwork with a lone blurred figure disappearing into an archway – only a pathetically bent tree and motionless black bird cohabit the snow-filled foreground. Another of the same location shows a line of waiting Hansom cabs, static except perhaps for the bent hoof of a horse or in the blackened vault to the left where an indistinct figure may be using the underbelly of the bridge as a urinoir. What could be more mundane? Witsen preserves this as an aside, something we perhaps won’t even notice. A night scene with several faceless figures along the river as it flows underneath an arch may at first seem like a departure, street lamps lighting the way into the distance. But these figures are disconnected, dissolving ghostlike into watery greys and muted browns. While these sombre scenes were being executed, Witsen’s house in Camden was serving as a short stay address for several friends from back home, who tightened the bonds of friendship by living the artist’s life together.

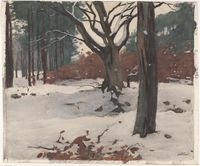

In the Netherlands, one can move quickly between city and countryside, and back. When he returned from London, Witsen decamped from Amsterdam to a country house his father had bought after the death of his mother and turned his gaze to the stillness of snowy woods. In a somewhat odd composition (again executed twice, once in watercolour and once in oil), the artist achieves a powerful stillness. This 1894 landscape portrays a big craggy old tree in the centre, with a more distant copse to the left, while a close-up bare trunk just right of centre disappearing out of our field of view acts as an awkward repoussoir. It does little, however, to frame the scene, almost rather bisecting it. The placement seems to reinforce randomness as opposed to balance. A similar enigmatic stillness is exuded by another painting showing a village huddled horizontally in the middle distance of a snowfield, sandwiched between grey sky and grey foreground. We recognize human habitation, but look in vain for any inviting warmth. This is a disquieting quiet. Contrast the pure joy Witsen felt in producing this art, as recorded in his letters, and the mystery only deepens. Catharsis perhaps for the loss of his mother age 13 and the later the suicide of his beloved sister? Even without psychologizing, we understand that something in such scenes spoke deeply to him.

After his return to Amsterdam, Witsen found that the messiness of Amsterdam streetscapes was a perfect carrier of his theme. His buoyant enthusiasm for dark, dank days in the city is revealed in a letter where he cites such atmosphere as the height of aesthetic beauty: “those big chunks of beautiful Amsterdam, with those rain clouds and that damp – lovely, lovely, lovely, there’s nothing like it.”

In paintings and prints from 1897 to 1913 depicting canal houses, backs of houses and urban quaysides from vantage points both hovering above and down below street level, Witsen injects a vacant stillness into out of the way scenes. High canal houses threaten to overwhelm little stick figures on the Damrak, who pass each other unawares, or in another painting where passers-by stand along the Krom Boomsloot as if holding a pose for a long camera exposure. Etches in high contrast black and white take the monochrome dull palette of oil and watercolour in another direction. It’s almost always winter, with leaden skies, snow lined buildings, and the jumbled masts of moored boats taking the place of bare tree branches of the earlier landscapes. The blackened windows of the houses, with or without white curtains or blinds, shut us out. A painting showing the backsides of houses on a canal in Amsterdam that Witsen painted from his boat-cum-atelier lovingly depicts nothing in particular – a drainpipe, a rag hanging to dry, some flower pots and stained brick. It somehow succeeds in bringing us closer to the gritty urban everyday world in its dilapidated, decaying silence. Where Israels and Breitner made great use of colour and daylight, chose female subjects in a boudoir or on horseback, and imbued their canvases with movement and drama, Witsen sticks to his muted palette, stasis, shadowy figures and grey weather aesthetic. It’s a beauty that one has to cultivate, gazing through the eyes of an artist who takes us to visit non-places. The most dramatic element of the exhibition is not an artwork at all, but an outdoors jacket, encrusted with the paint Witsen wiped on his sleeve while working. This marvellous object animates our image of the painter at work like nothing else.

The top floor of the villa is given to the photographs of the 1890s, many of them seen in passing in the rooms below. These show the real-life figures who peopled his life: the writers and artists of the eighties movement, his first wife Betsy and their two children. But the most intriguing are those of Witsen himself. A series of self-portraits taken at different stages of his young life brings us face to face. Enchantingly, we can get so close to the artist through the medium of glass plate photography that we see every pore, every freckle and every hair on his face. His facial expression is unlike the closed or distant looks of Betsy, the children and his artist/writer friends as they stare almost confrontationally back at us. It's an open expression, with a look of mild surprise or deeply relaxed calm. The most arresting is a full-length self-portrait of Witsen, with his painting gear slung over his shoulder, wearing wooden shoes and holding a lit cigarette, ready and excited to set to work outdoors. The artist of the troubling rather than tranquil stillness stands on the threshold of a new day. And the visitor to this exhibition carries away a life-long affinity for Witsen's art and way of seeing the world, which is the best museum experience one can ask for.